How Yiddish Writers Became Yiddish Writers

Narrations on the Choice of Yiddish in Autobiographical Writings after Peretz

Carmen Reichert (Augsburg University)

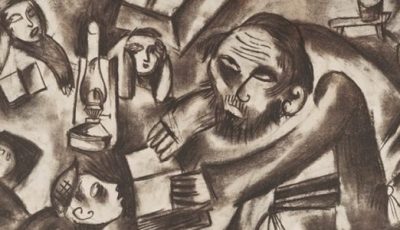

It should come as no surprise that literary autobiographies essentially tell us how writers became writers. From Rousseau’s Confessions to Goethe’s Bildungsroman – lire and écrire – an author’s reading lists and their first attempts at writing are crucial topoi to the genre. But the Yiddish writers of the early twentieth century did not grow up with the knowledge that their mother tongue was a literary language. Hebrew and not Yiddish was the language of learning in private schools for Jewish boys. This is why Yiddish writing in the early twentieth-century developed somewhere between the traditional, Hebrew-dominated education system of Cheders and Yeshivas and non-Jewish libraries. According to tradition, written Yiddish texts were primarily intended for women and uneducated men. Therefore, male and female writers developed different writing strategies when writing Yiddish: Whereas women could trace their writings back to early Yiddish autobiographies such as Glikl of Hameln’s “Zikhroynes” (Memories), men preferred to follow Western European traditions. Yiddish autobiographies often link the personal lives of their writers to the history of Yiddish. For example, when Sholem Aleichem compares his life to the market (“yarid”), he simultaneously commits his voice to the “market language” of Yiddish. I. L. Peretz, the “father” of the Yiddish literature, was particularly influential in this context. Not only did he encourage writers to switch to their native language, his autobiography “Mayne zikhroynes” (My Memoirs), which draws inspiration from Romanticism, inspired a great number of autobiographical texts from younger writers.

14 May 2019 – 5:30 PM, the library of CEFRES (Na Florenci 3, Prague 1)